| English

--> engmovie-000

--> e-engmov-023-2 |

Same

CN |

|

|

|

A

downloaded movie used eMule with Morricone's music

|

|

e-engmov-023-2

|

|

Allonsanfan

(1973) film and music's research

|

The

movie was provided by Lajiao

|

|

|

|

|

Relative

music site

|

|

|

IMDB(English)

|

|

|

IMDB(Chinese)

|

|

|

Note

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Our

prompt:

In order to understand the Movie, we have to study a few information |

|

001-Italy

history

|

|

| Italy,

united in 1861, has significantly contributed to the cultural

and social development of the entire Mediterranean area. Many

cultures and civilizations have existed there since prehistoric

times.

Culturally

and linguistically, the origins of Italian history can be

traced back to the 9th century BC, when earliest accounts

date the presence of Italic tribes in modern central Italy.

Linguistically they are divided into Oscans, Umbrians and

Latins. Later the Latin culture became dominant, as Rome

emerged as dominant city around 350 BC. Other pre-Roman

civilizations include Magna Graecia in Southern Italy and

the earlier Etruscan civilization, which flourished between

900 and 100 BC in the Center North.

After

the Roman Republic and Empire that dominated this part of

the world for many centuries came an Italy whose people

would make immeasurable contributions to the development

of European philosophy, science, and art during the Middle

Ages and the Renaissance. Dominated by city-states for much

of the medieval and Renaissance period, the Italian peninsula

also experienced several foreign dominations. Parts of Italy

were annexed to the Spanish, the Austrian and Napoleon's

empire, while the Vatican maintained control over the central

part of it, before the Italian Peninsula was eventually

liberated and unified amidst much struggle in the 19th and

20th centuries.

|

| |

|

|

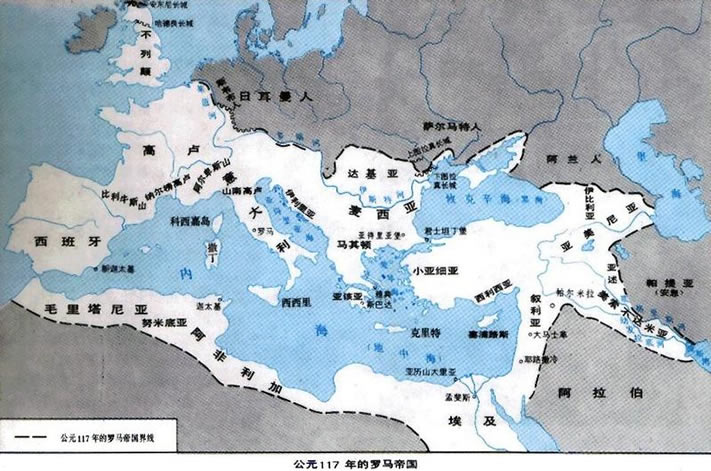

The

Roma empire in 117

|

|

|

|

The

split of Roma empire and perdition of West Roma empire

|

| |

Foreign

domination (1559 to 1814)

Main article: Early Modern Italy

The War of the League of Cambrai was a major conflict in the

Italian Wars. The principal participants of the war were France,

the Papal States, and the Republic of Venice; they were joined,

at various times, by nearly every significant power in Western

Europe, including Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom

of England, the Kingdom of Scotland, the Duchy of Milan, Florence,

the Duchy of Ferrara, and the Swiss.

The

history of Italy in the Early Modern period was characterized

by foreign domination: Following the Italian Wars (1494

to 1559), Italy saw a long period of relative peace, first

under Habsburg Spain (1559 to 1713) and then under Habsburg

Austria (1713 to 1796). During the Napoleonic era, Italy

was a client state of the French Republic (1796 to 1814).

The Congress of Vienna (1814) restored the situation of

the late 18th century, which was however quickly overturned

by the incipient movement of Italian unification.

The

Black Death repeatedly returned to haunt Italy throughout

the 14th to 17th centuries. The plague of 1575–77 claimed

some 50,000 victims in Venice.[3] In the first half of the

17th century a plague claimed some 1,730,000 victims, or

about 14% of Italy’s population.[4] The Great Plague of

Milan occurred from 1629 through 1631 in northern Italy,

with the cities of Lombardy and Venice experiencing particularly

high death rates. In 1656 the plague killed about half of

Naples' 300,000 inhabitants.[5]

Unification

(1814 to 1861)

Main article: Italian unification

Italian unification process.The Risorgimento was the political

and social process that unified different states of the

Italian peninsula into the single nation of Italy.

It is

difficult to pin down exact dates for the beginning and

end of Italian reunification, but most scholars agree that

it began with the end of Napoleonic rule and the Congress

of Vienna in 1815, and approximately ended with the Franco-Prussian

War in 1871, though the last "città irredente"

did not join the Kingdom of Italy until the Italian victory

in World War I.

[edit]

Monarchy, Fascism and World Wars (1861-1945)

Main article: History of Italy as a monarchy and in the

World Wars

Italy became a nation-state belatedly — on March 17, 1861,

when most of the states of the peninsula were united under

king Victor Emmanuel II of the Savoy dynasty, which ruled

over Piedmont. The architects of Italian unification were

Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, the Chief Minister of Victor

Emmanuel, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, a general and national

hero. Rome itself remained for a decade under the Papacy,

and became part of the Kingdom of Italy only on September

20, 1870, the final date of Italian unification. The Vatican

is now an independent enclave surrounded by Italy, as is

San Marino.

(here)

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Wienna

meeting in 1814(here)

|

|

|

|

|

Italy

in 1815-1870 (here)

|

| |

|

Carbonari

|

|

The

Carbonari ("charcoal burners"[1]) were groups

of secret revolutionary societies founded in early

19th-century Italy. Their goals were patriotic and

liberal and they played an important role in the Risorgimento

and the early years of Italian nationalism.

Organization

They were organized in the fashion of Freemasonry,

broken into small cells scattered across Italy. They

sought the creation of a liberal, unified Italy.

The

membership was separated into two classes—apprentice

and master. There were two ways to become a master,

through serving as an apprentice for at least six

months[2] or by being a Freemason on entry.[3] Their

initiation rituals were structured around the trade

of charcoal-selling, hence their name.

|

|

|

History

Although it is not clear where they were originally established,[4]

they first came to prominence in the Kingdom of Naples during

the Napoleonic wars.[5]

They

began by resisting the French occupiers, notably Joachim

Murat, the Bonapartist King of Naples. However, once the

wars ended, they became a nationalist organisation with

a marked anti-Austrian tendency and were instrumental in

organising revolution in Italy in 1820–1821 and 1831. The

1820 revolution began in Naples against King Ferdinand I

of the Two Sicilies, who was forced to make concessions

and promise a constitutional monarchy. This success inspired

Carbonari in the north of Italy to revolt too. In 1821,

the Kingdom of Sardinia obtained a constitutional monarchy

as a result of Carbonari actions, as well as other reforms

of liberalism. However, the Holy Alliance would not tolerate

this state of affairs and in February, 1821, sent an army

to crush the revolution in Naples. The King of Sardinia

also called for Austrian intervention. Faced with an enemy

overwhelmingly superior in number, the Carbonari revolts

collapsed and their leaders fled into exile. In 1830, Carbonari

took part in the July Revolution in France. This gave them

hope that a successful revolution might be staged in Italy.

A bid in Modena was an outright failure, but in February

1831, several cities in the Papal States rose up and flew

the Carbonari tricolour. A volunteer force marched on Rome

but was destroyed by Austrian troops who had intervened

at the request of Pope Gregory XVI. After the failed uprisings

of 1831, the governments of the various Italian states cracked

down on the Carbonari, who now virtually ceased to exist.

The more astute members realised they could never take on

the Austrian army in open battle and joined a new movement,

Giovane Italia ("Young Italy") led by the nationalist

and Freemason Giuseppe Mazzini.(here)

|

|

-------------------------------------------------------------

|

|

Legend

hero Giuseppe Garibaldi

|

| Giuseppe

Garibaldi

(July 4, 1807 – June 2, 1882) was an Italian military and

political figure. In his twenties, he joined the Carbonari

Italian patriot revolutionaries, and had to flee Italy after

a failed insurrection. Garibaldi took part in the War of the

Farrapos and the Uruguayan Civil War leading the Italian Legion,

and afterwards returned to Italy as a commander in the conflicts

of the Risorgimento.

He has

been dubbed the "Hero of the Two Worlds" in tribute

to his military expeditions in both South America and Europe.[1]

He is considered an Italian national hero.

|

|

Second

Italian War of Independence

Garibaldi, in a popular colour lithographGaribaldi returned

again to Italy in 1854. Using a legacy from the death of his

brother, he bought half of the Italian island of Caprera (north

of Sardinia), devoting himself to agriculture. In 1859, the

Second Italian War of Independence (also known as the Austro-Sardinian

War) broke out in the midst of internal plots at the Sardinian

government. Garibaldi was appointed major general, and formed

a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps (Cacciatori

delle Alpi). Thenceforth, Garibaldi abandoned Mazzini's republican

ideal of the liberation of Italy, assuming that only the Piedmontese

monarchy could effectively achieve it.

With

his volunteers, he won victories over the Austrians at Varese,

Como, and other places.

Garibaldi

was however very displeased as his home city of Nice (Nizza

in Italian) was surrendered to the French, in return for

crucial military assistance. In April 1860, as deputy for

Nice in the Piedmontese parliament at Turin, he vehemently

attacked Cavour for ceding Nice and the County of Nice (Nizzardo)

to Louis Napoleon, Emperor of the French. In the following

years Garibaldi (with other passionate Nizzardo Italians)

promoted the Irredentism of his Nizza, even with riots (in

1872).

Campaign

of 1860

See also: Expedition of the Thousand

On January 24, 1860, Garibaldi married an 18-year-old Lombard

noblewoman, Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding

ceremony, however, she informed him that she was pregnant

with another man's child. As a result, Garibaldi left her

the same day.[citation needed]

At the

beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina and Palermo

in the independent and peaceful Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered about

a thousand volunteers (practically all northern Italians,

and called i Mille (the Thousand), or, as popularly known,

the Redshirts) in two ships, and landed at Marsala, on the

westernmost point of Sicily, on May 11.

Swelling

the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels,

Garibaldi led 800 of his volunteers to victory over a 1500-strong

enemy force on the hill of Calatafimi on May 15. He used

the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge;

he had seen that the hill on which the enemy had taken position

was terraced, and the terraces gave shelter to his advancing

men. Although small by comparison with the coming clashes

at Palermo, Milazzo and Volturno, this battle was decisive

in terms of establishing Garibaldi's power in the island;

an apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant

Nino Bixio, Qui si fa l'Italia o si muore, that is, Here

we either make Italy, or we die. In reality, the Neapolitan

forces were ill guided, and most of its higher officers

had been bought out. The next day, he declared himself dictator

of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He

advanced then to Palermo, the capital of the island, and

launched a siege on May 27. He had the support of many of

the inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison, but before

the city could be taken, reinforcements arrived and bombarded

the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral

intervened and facilitated an armistice, by which the Neapolitan

royal troops and warships surrendered the city and departed.

Garibaldi

had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and

the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong

that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized, even the Neapolitan

court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the

east of the island. There was a ferocious and difficult

battle at Milazzo, but Garibaldi won through. By the end

of July, only the citadel resisted.

Portrait of Giuseppe Garibaldi.Having finished the conquest

of Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina, with the help

of the British Navy, and marched northward. Garibaldi's

progress was met with more celebration than resistance,

and on September 7 he entered the capital city of Naples,

by train. Despite taking Naples, however, he had not to

this point defeated the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi's volunteer

army of 24,000 was not able to defeat conclusively the reorganized

Neapolitan army (about 25,000 men) on September 30 at the

Battle of Volturno. This was the largest battle he ever

fought, but its outcome was effectively decided by the arrival

of the Piedmontese Army. Following this, Garibaldi's plans

to march on to Rome were jeopardized by the Piedmontese,

technically his ally but unwilling to risk war with France,

whose army protected the Pope. (The Piedmontese themselves

had conquered most of the Pope's territories in their march

south to meet Garibaldi, but they had deliberately avoided

Rome, his capital.) Garibaldi chose to hand over all his

territorial gains in the south to the Piedmontese and withdrew

to Caprera and temporary retirement. Some modern historians

consider the handover of his gains to the Piedmontese as

a political defeat, but he seemed willing to see Italian

unity brought about under the Piedmontese crown. The meeting

at Teano between Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II is the

most important event in modern Italian history, but is so

shrouded in controversy that even the exact site where it

took place is in doubt.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Garibaldi

and his volunteer

|

Giuseppe

Garibaldi

|

Garibaldi'sstatuary

in Milan

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

002-Character

and events with the movie

|

| |

|

2-1

Robespierre

|

|

|

Maximilien

Fran?ois Marie Isidore de Robespierre (IPA: [maksimilj??

f?ɑ?swa ma?i izid?? d? ??b?spj??]) (6 May 1758 – 28 July

1794) is one of the best-known and most influential figures

of the French Revolution. He largely dominated the Committee

of Public Safety and was instrumental in the period of the

Revolution commonly known as the Reign of Terror, which

ended with his arrest and execution in 1794.

|

|

|

Robespierre(1758—1794)

|

July

27, 1794 (9 Thermidor), Robespierre was executed by the guillotine |

| Robespierre

was influenced by 18th century Enlightenment philosophes such

as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Montesquieu, and he was a capable

articulator of the beliefs of the left-wing bourgeoisie. He

was described as physically unimposing and immaculate in attire

and personal manners. His supporters called him "The

Incorruptible", while his adversaries called him the

"Tyrant" and dictateur sanguinaire (bloodthirsty

dictator)....(here) |

| |

|

2-2

Jacobin

|

Member

of an extremist republican club of the French Revolution founded

in Versailles 1789. Helped by Danton's speeches, they proclaimed

the French republic, had the king executed, and overthrew

the moderate Girondins 1792–93. Through the Committee of Public

Safety, they began the Reign of Terror, led by Robespierre.

After his execution in 1794, the club was abandoned and the

name ‘Jacobin’ passed into general use for any left-wing extremist.(here)

|

|

2-3

Mayflower and Thanksgiving

|

| In

1620, some wealthy Englishmen hired the Mayflower and the

Speedwell to make a trip to start a colony in Northern Virginia.

The Speedwell turned out to be a leaky ship, and so was unable

to make the famous voyage with the Mayflower.

Christopher

Jones was the captain of the Mayflower when it took the

Pilgrims to New England in 1620. They came to the tip of

Cape Cod (Massachusetts) on November 11, 1620.

Mayflower

was a very common ship name, and other ships called the

Mayflower made trips to New England; but none of them were

the same ship that brought the Pilgrims to America.

The

Mayflower stayed in America that winter, and it suffered

the effects of the first winter just as the Pilgrims did,

with almost half dying. The Mayflower set sail for home

on April 5, 1621, arriving back May sixth. The ship made

a few more trading runs, to Spain, Ireland, and lastly to

France. However, Captain Christopher Jones died shortly

thereafter, and was buried in England.

The

exact size of the Mayflower is unknown. No pictures, paintings,

or detailed description of the Mayflower exist today. However

it is estimated the size of the Mayflower was about 113

feet long from the back rail to the front. A duplicate of

the Mayflower, called the Mayflower II, is in Plymouth,

Mass. Today it is a tourist attraction, and available for

touring.

The

voyage from Plymouth, England to Plymouth Harbor is about

2,750 miles, and took the Mayflower 66 days. The Mayflower

left England with 102 passengers, including three pregnant

women, and a crew of unknown number. One child was born

at sea. After the Mayflower had arrived and was anchored

in Provincetown Harbor off the tip of Cape Cod, Susanna

White gave birth to a son. The Mayflower then sailed across

the bay to Plymouth Harbor. There, Mary Allerton gave birth

to a stillborn son. One passenger died while the Mayflower

was at sea--a young man named William Butten, a servant-apprentice

to Dr. Samuel Fuller. The death occurred just three days

before land was sighted. One Mayflower crew member also

died at sea, but his name is not known. The men of the Mayflower

wrote "The Mayflower Compact", a set of laws for

the new colony. This was the first time that immigrants

to the new country had set down rule of the majority. It

is still used today. The place they stayed was called the

Plymouth Colony.

The Mayflower's Voyage :

DEPARTURE:

The Mayflower left Plymouth, England on September 6, 1620

ARRIVAL:

The Mayflower crew sighted land off Cape Cod on November

9, 1620, and first landfall was made November 11, 1620.

DISTANCE

AND TIME: The voyage from Plymouth, England to Plymouth

Harbor is about 2,750 miles, and took the Mayflower 66 days.

NUMBER

OF PASSENGERS: The Mayflower left England with 102 passengers,

including three pregnant women, and a crew of unknown number.

While the Mayflower was at sea, Elizabeth Hopkins gave birth

to a son which she named Oceanus. After the Mayflower had

arrived and was anchored in Provincetown Harbor off the

tip of Cape Cod, Susanna White gave birth to a son, which

she named Peregrine (which means "one who has made

a journey"). The Mayflower then sailed across the bay

and anchored in Plymouth Harbor. There, Mary Allerton gave

birth to a stillborn son. One passenger died while the Mayflower

was at sea--a youth named William Butten, a servant-apprentice

to Dr. Samuel Fuller. The death occurred just three days

before land was sighted. One Mayflower crew member also

died at sea, but his name is not known.

|

|

|

|

|

Plymouth

is located in Boston Harbor "Mayflower,"

a copy of the yacht.

|

Pilgrims

from the United Kingdom in order to thank the Indians

for their support during difficult times and God for

their "gift" is the year (1620) the fourth

Thursday in November, they made delicious turkey hunting,

Indian hospitality .1941, the U.S. Congress officially

set at each of its "Thanksgiving Day"

|

|

|

|

The

Mayflower at Sea". By Gilbert Margeson (1852-1940).(here)

|

The

Voyage of the Mayflower", steel-plate engraving

based on the painting by John Marshall the Elder,

later coloration (here)

|

|

| |

| MYTH:

The first Thanksgiving was in 1621 and the pilgrims celebrated

it every year thereafter.

FACT:

The first feast wasn't repeated, so it wasn't the beginning

of a tradition. In fact, the colonists didn't even call

the day Thanksgiving. To them, a thanksgiving was a religious

holiday in which they would go to church and thank God for

a specific event, such as the winning of a battle. On such

a religious day, the types of recreational activities that

the pilgrims and Wampanoag Indians participated in during

the 1621 harvest feast--dancing, singing secular songs,

playing games--wouldn't have been allowed. The feast was

a secular celebration, so it never would have been considered

a thanksgiving in the pilgrims minds.

MYTH:

The original Thanksgiving feast took place on the fourth

Thursday of November.

FACT:

The original feast in 1621 occurred sometime between September

21 and November 11. Unlike our modern holiday, it was three

days long. The event was based on English harvest festivals,

which traditionally occurred around the 29th of September.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt set the date for Thanksgiving

to the fourth Thursday of November in 1939 (approved by

Congress in 1941). Abraham Lincoln had previously designated

it as the last Thursday in November, which may have correlated

it with the November 21, 1621, anchoring of the Mayflower

at Cape Cod.

MYTH:

The pilgrims wore only black and white clothing. They had

buckles on their hats, garments, and shoes.

FACT:

Buckles did not come into fashion until later in the seventeenth

century and black and white were commonly worn only on Sunday

and formal occasions. Women typically dressed in red, earthy

green, brown, blue, violet, and gray, while men wore clothing

in white, beige, black, earthy green, and brown.

MYTH:

The pilgrims brought furniture with them on the Mayflower.

FACT:

The only furniture that the pilgrims brought on the Mayflower

was chests and boxes. They constructed wooden furniture

once they settled in Plymouth.

MYTH:

The Mayflower was headed for Virginia, but due to a navigational

mistake it ended up in Cape Cod Massachusetts.

FACT:

The Pilgrims were in fact planning to settle in Virginia,

but not the modern-day state of Virginia. They were part

of the Virginia Company, which had the rights to most of

the eastern seaboard of the U.S. The pilgrims had intended

to go to the Hudson River region in New York State, which

would have been considered "Northern Virginia,"

but they landed in Cape Cod instead. Treacherous seas prevented

them from venturing further south (here)

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

003-Giuseppe

Verdi

|

| |

| Giuseppe

Fortunino Francesco Verdi (Italian

pronunciation: [d?u?z?pp?e ?verdi]; October 9 or 10, 1813

– January 27, 1901) was an Italian Romantic composer, mainly

of opera. He was one of the most influential composers of

the 19th century. His works are frequently performed in opera

houses throughout the world and, transcending the boundaries

of the genre, some of his themes have long since taken root

in popular culture - such as "La donna è mobile"

from Rigoletto, "Va, pensiero" (The Chorus of the

Hebrew Slaves) from Nabucco, "Libiamo ne' lieti calici"

(The Drinking Song) from La traviata and Triumphal March from

Aida. Although his work was sometimes criticized for using

a generally diatonic rather than a chromatic musical idiom

and having a tendency toward melodrama, Verdi’s masterworks

dominate the standard repertoire a century and a half after

their composition. |

|

| |

Works

Main article: List of compositions by Giuseppe Verdi

Verdi's operas, and their date of première are:

Oberto,

November 17, 1839

Un giorno di regno, September 5, 1840

Nabucco, March 9, 1842

I Lombardi alla prima crociata, February 11, 1843

Ernani, March 9, 1844

I due Foscari, November 3, 1844

Giovanna d'Arco, February 15, 1845

Alzira, August 12, 1845

Attila, March 17, 1846

Macbeth, March 14, 1847

I masnadieri, July 22, 1847

Jérusalem (a revision and translation of I Lombardi alla

prima crociata) November 26, 1847

Il corsaro, 25 October 1848

La battaglia di Legnano, January 27, 1849

Luisa Miller, December 8, 1849

Stiffelio, November 16, 1850

Rigoletto, March 11, 1851

Il trovatore, January 19, 1853

La traviata, March 6, 1853

Les vêpres siciliennes, June 13, 1855

Simon Boccanegra, March 12, 1857

Aroldo (A major revision of Stiffelio), August 16, 1857

Un ballo in maschera, February 17, 1859

La forza del destino, November 10, 1862

Don Carlos, March 11, 1867

Aida, December 24, 1871

Otello, February 5, 1887

Falstaff, February 9, 1893

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Doc.31,2009

|

| |

| |

| |