| Italian

Horror Movies

The

words ??Italian horror?? are enough to send shivers of excitement

up the spines of hardcore horror fans around the globe.

Sure, these movies may sometimes contain lackluster acting

and bad dubbing, but Italian horror films are also known

for brutal violence and plenty of gore (with neither women

nor children being spared). Often containing surreal scenes

and plotlines, Italian horror movies tend to be a breath

of fresh air when compared to their more formulaic cousins

from the United States.

While

the scariest Italian horror tends to be found in the films

of the ??70s and ??80s, the tradition of Italian horror movies

stretches back all the way to the ??50s. In recent years,

the number of genre films have suffered a notable decline,

but the occasional brutal gem still gets made.

Below,

I have attempted to give an overview of the Italian horror

movie industry. While this list is by no means complete,

it should serve as a guide to some of the more essential

Italian horror movies and Italian horror directors. If you

see even one movie on this list?Cand enjoy it?Cthen I??ll feel

as though my efforts haven??t been in vain.

Origins

of the Italian Horror Movie

To find

the origins of Italian horror, we must journey back to 1956.

It was in this year that director and sculptor Riccardo

Freda made I Vampiri (also known as The Devil??s Commandment),

a film revolving around young women being abducted and having

their blood drained. While the film was a box office disappointment,

it did pave the way for more successful Italian horror movies.

It should also be noted that Freda left the project with

two days to go, and the film was completed by a cameraman

named Mario Bava (who would himself go on to become one

of the best-known Italian horror directors).

In 1960,

Renato Polselli directed The Vampire and the Ballerina,

but it wasn??t met with much enthusiasm. At this point, the

Italian horror movement looked to be over before it even

got started. That all changed later in 1960, however, as

Mario Bava exploded onto the scene with The Mask of Satan

(also known as Black Sunday in the U.S.). Considered one

of the all-time scariest Italian horror films, The Mask

of Satan told the story of a witch who returned from the

grave to seek revenge on the descendents of her killers.

The

film was a hit in Italy and abroad, and many critics pointed

to Bava??s intricate use of light and shadow to create mood

and tension. The film launched Bava??s directorial career,

and it also served as a star vehicle for actress Barbara

Steele (who would star in a total of nine Italian horror

movies).

With

the origin of Italian horror now firmly set, the genre was

allowed to flourish throughout the rest of the ??60s. Riccardo

Freda (under the pseudonym Robert Hampton) returned to the

horror genre with The Terror of Dr. Hitchcock (aka The Horrible

Dr. Hichcock) in 1962 and a sequel, Ghost, in 1963. Antonio

Margheriti made Castle of Blood in 1964, and later that

year the Italian horror director would also release The

Virgin of Nueremburg and The Long Hair of Death.

Mario

Bava was especially busy during this period. Coming off

his success with The Mask of Satan, Bava followed up with

The Evil Eye (1961), Black Sabbath (1963), What!The Whip

and the Body AKA (1963), Blood and Black Lace (1964), and

Kill, Baby, Kill (1968). The latter, a story about a series

of murders in a small village, is considered another high

point of the Italian horror movie genre.

Rise

of the Giallo

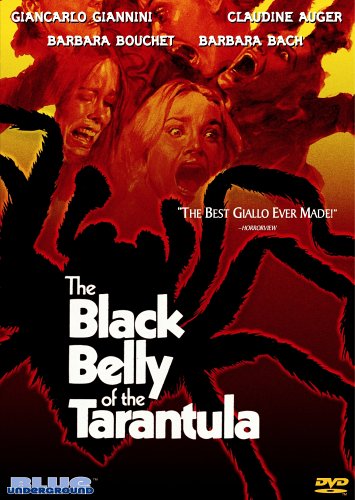

Giallo,

a style of Italian horror film known for its combination

of sex and violence, emerged onto the cinematic landscape

in the ??70s. In Italian, the word giallo means ??yellow,??

which indicates its origins in cheap paperback mystery novels

with yellow covers. In English, the word has come to mean

an entire range of Italian horror films, especially those

with unique musical scores (often featuring the works of

composer Ennio Morricone or the rock band Goblin), stylized

scenes of blood and mayhem, nudity, and creative camerawork.

While many of these films retained the element of mystery

found in their literary predecessors, the conventions of

the slasher film were also added. Themes of paranoia and

madness are also quite common. In their native land, these

films are known as ??Giallo all??italiana?? or ??Thrilling.??

While

these giallo films were separate from those of the gothic-horror

genre, the two began to combine over time. This resulted

in even more creative cinematic endeavors, and a legion

of devoted fans flocked to such films. Many giallo were

not initially well-received in the U.S., however, as the

films were often poorly dubbed and re-edited. But their

fan base grew over time, establishing the reputations of

Italian horror directors such as Lucio Fulci, Umberto Lenzi,

Pupi Avati, Dario Argento, Mario Bava, Sergio Martino and

Aldo Lado.

The

first giallo film, The Girl Who Knew Too Much, actually

appeared in 1962, and it was made by none other than Mario

Bava. Now a veteran director, the former cameraman for Riccardo

Freda cemented the popularity of the genre in 1964 when

he made Blood and Black Lace (or Six Women for an Assassin).

While containing a whodunit aspect, the film was also shockingly

violent for the time. Bava would later make the giallo films

Five Dolls for an August Moon (1970) and Bay of Blood (or

Twitch of the Death Nerve) (1971).

Of all

the Italian horror directors, the one to become best-known

to international audiences was Dario Argento. With his unique

visual style and over-the-top violence, Argento brought

giallo into the Italian mainstream and provided a face for

the global horror community. His first film, Bird With the

Crystal Plumage, was released in 1970 and inspired a number

of Italian horror movies containing the names of animals.

Argento??s next films were Cat o?? Nine Tails and Four Flies

on Grey Velvet, both released in 1971.

Dario

Argento made Deep Red (or Profondo Rosso) in 1976. It took

giallo films to new heights, and while it did retain a certain

narrative structure, Argento was clearly more interested

in exploring visual symbology throughout the movie. The

trademark Dario Argento violence is still present in Deep

Red, as teeth are bashed out, heads are decapitated, and

one unlucky victim is severely scalded in a bathtub full

of water.

Giallo

films would continue to be popular throughout the ??70s and

??80s, with the following titles being some of the best examples

of the genre:

The

Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (aka Next!) (Sergio Martino,

1971)

Don??t Torture a Duckling (Lucio Fulci, 1972)

Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (Sergio

Martino, 1972)

What Have You Done to Solange? (Massimo Dallamano, 1972)

Torso (Sergio Martino, 1973)

Eyeball (Umberto Lenzi, 1974)

A Dragonfly for Each Corpse (Leon Klimovsky, 1974)

The Psychic (Lucio Fulci, 1977)

Tenebrae (Dario Argento, 1982)

The New York Ripper (Lucio Fulci, 1982)

Deliria (Michele Soavi, 1987)

Opera (Dario Argento, 1988)

The Golden Age of Italian Horror

Movies

The

Italian horror movement entered its golden age with the

release of Dario Argento??s Suspiria in 1976. This was followed

up by his equally influential Inferno in 1980. During this

period, many Italian horror films were also turning to themes

of zombies and demonic possession, obviously inspired by

movies such as Dawn of the Dead and The Exorcist. Lucio

Fulci??s Zombi II (1979), for example, remains a film which

is still talked about due to its high gore content and the

surrealistic showdown between a zombie and a shark. Gates

of Hell, also known as City of the Living Dead (1980), is

another Lucio Fulci film which still receives attention

from fans of Italian horror movies. Exceedingly graphic,

Gates of Hell features a scene in which a character vomits

up her own intestines (in reality, the actress actually

vomited up sheep intestines).

As the

zombie genre continued to grow in popularity, a number of

cannibal-themed films also began to get made. The most notorious

of these is Cannibal Holocaust, made in 1980 by Ruggero

Deodato. In it, a documentary crew heads into the Amazon

jungle to search for a mythical tribe of cannibals. In order

to get more interesting footage, they take to raping, torturing

and killing the natives they encounter. Besides the extreme

violence simulated in the film, Cannibal Holocaust is also

known for showing the real-life deaths of a number of animals.

Deodato continued to work in the genre after this film,

with 1993??s Washing Machine widely regarded as his other

notable work.

Mario

Bava??s son, Lamberto Bava, also made his mark with films

such as Demons (1985) and Demons II (1987). Lamberto Bava

outdid those who were ripping off The Exorcist or Dawn of

the Dead or by combining the themes of zombies and demonic

possession into one film.

The

Decline of Italian Horror Movies

As the 1990s rolled around, the momentum of the Italian

horror film had started to slow. Dario Argento tried his

hand at Hollywood, but the results were disappointing. Mario

Bava passed away in 1980, and Lucio Fulci died in 1996.

One

of the few significant Italian horror movies to be released

in the ??90s was Cemetery Man (aka Dellamorte Dellamore),

directed by Michele Soavi. Starring Rupert Everett, Cemetery

Man tells the story of a cemetery caretaker whose corpses

won??t stay in the ground. Filled with plenty of nudity,

gore, and dark comedy, many credit it with single-handedly

keeping the Italian horror movie alive during the decade.

But

by the dawn of the new millennium, the state of the genre

was rapidly deteriorating. Dario Argento??s movies lacked

their former visceral power, Sergio Martino had transitioned

to working in Italian television, and even Lamberto Bava

expressed a preference for making movies aimed at children.

At the

same time, the mainstream Italian cinema was experiencing

a resurgence led by men such as Giuseppe Tornatore, Gabriele

Salvatore, Roberto Benigni and Nanni Moretti. This, coupled

with the explosion of the Asian horror market, served to

diminish the popularity of Italian horror films both at

home and on the international market.

As of

this writing, the horror genre has been somewhat forgotten

in Italian cinema. While fans can still choose from hundreds

of ??classics,?? anyone looking for new Italian horror films

will have to wait patiently until the next Argento, Bava

or Fulci comes along and reignites the industry.(Here)

|